The unheard voice of LGBT youth

February 23, 2018

Almost three years after the legalization of same-sex marriage in all 50 states of the U.S., the issue of societal discrimination against the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community has failed to go away, and in the halls of BFA, the situation is no different.

92 percent of LGBT youth say they hear negative messages about being LGBT, and one of the top sources that they hear this from is school, according to the Human Rights Campaign (HRC).

The issue of discrimination against the LGBT community is prevalent throughout the country, with a Colorado baker refusing to bake a wedding cake for a gay couple, and there are still no laws preventing LGBT discrimination in the workplace in 28 states (HRC).

Lia Callahan (‘19), a student who openly identifies as transgender, had much to say when it came to her experience in the LGBT community at BFA.

“There definitely is not the best environment at BFA. I remember when I first came out, I think like the most memorable thing, I was walking down the street with my friends, and a teenager from BFA stuck their head out the window, yelled something like, ‘Ew’, and threw a cup full of soda from McDonald’s at us,” Callahan said.

According to the 2015 Vermont Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 88 percent of high school students described themselves as heterosexual, while only eight percent described themselves as bisexual, gay or lesbian and four percent as unsure.

“Some people, it’s just not worth risking that sort of backlash to come out and I think that’s where people get stigmas from, cause they get it from their friends. They get it from their family, but they don’t actually see it. They don’t actually experience it at BFA because it’s … one group of people. one demographic,” Callahan said.

Without the exposure at BFA that the LGBT community needs, many people fail to learn and educate themselves about what these minorities are truly like. Sticking around with the same group of people, with the same ideas and experiences, allows students to miss the true learning of the world’s culture.

Elijah Church, one of BFA’s special educators, co-advises the Gay, Lesbian or Whatever (GLOW) Club. It seems he has a similar understanding of the school’s atmosphere when talking about GLOW.

“I think it’s perceived as a gay club, so I think a lot of people don’t show up because it’s just for gay people, in their mind,” Church said.

The perception of students can only be changed with exposure, and with the school climate right now, there doesn’t seem to be much exposure going on. Anything associated with the LGBT community, for example GLOW, gives off the wrong impression to students who don’t fully understand.

As of December 2016, states like Texas, Louisiana, South Carolina, and five others, have laws restricting teachers and staff from talking about LGBT issues at school, according to Human Rights Watch.

Vermont isn’t one of those states and allows for the discussion of LGBT issues to happen.

“I don’t think you have to necessarily bring up the politics that come around with [LGBT issues], but I do think there’s a need to just talk about what it is or how it exists. Like, I think health class would be a really great place to talk more about sexuality and gender identity,” Callahan said.

By opening up the curriculum and teaching more about the issues and discrimination surrounding the LGBT community, the whole community would feel more inclusive, as well as diminish the stereotypes and stigmas.

“I think [BFA] was a better experience than what I expected it was gonna be. But I think by just not doing anything crazy and just acting like a normal teenager-being a normal teenager-people are like, ‘Oh, so it’s not that crazy’, like it’s not like something weird. It’s just this person went to becoming this person and nothing was that crazy about it,” Callahan said.

Callahan’s experience with her peers’ evolving mindset about what it’s truly like to be transgender is a case to prove that the school needs more exposure and education on the LGBT community. If students opened their minds after learning more about who Callahan is, imagine the change that can be made through one lesson taught about LGBT issues in a classroom.

Being an ally himself, Church understands the importance of supporting and accepting LGBT youth for who they are. Being surrounded by allies can easily change a person’s life.

“People that are in any minority, I think … can feel ostracized and separated from the community as a whole and allies help remind them [that] they’re not actually different from anybody else,” Church said.

With not as many students showing their support for the LGBT community at BFA, Franklin County’s LGBT youth can feel afraid or unsure about being themselves. Living in such a way can be dangerous for one’s mental health.

Outright Vermont compared the 2013 and 2015 results from the Vermont Youth Risk Behavior Survey, and found several pieces of data that support the idea that the effect of LGBT discrimination is taking a toll on Vermont high school students. In 2013, 32 percent of LGBT youth made a suicide plan and in the 2015 survey, the number had risen to 40 percent.

The results also showed that in 2013, 36 percent of LGBT youth admitted to being bullied at school and in 2015, the number of the same youth being bullied rose to 40 percent. The most moving data found, was that in 2013, 49 percent of LGBT youth noted that they felt sad for two weeks or more, and in 2015, the number became 60 percent of LGBT youth.

All of these trends, however, could be preventable.

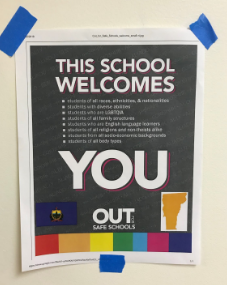

Given the documented increases in bullying incidents reported, and the increase in depression among LGBT youth, BFA should be paying attention to increasing education and support for these students if the school really wants every student to feel safe and welcome.

With the lack of LGBT education and exposure that BFA allows for, it doesn’t seem that the effort is being made to lower the percentage of students who feel discriminated against.

“If [BFA] would allow a little bit more exposure, it would be a lot easier. But I think … they talk about it, but they don’t really let us talk about it. …We’re not getting the exposure that we need for people to realize that it’s not this crazy thing,” Callahan said.