Survey Results Show More Female Depression

December 20, 2016

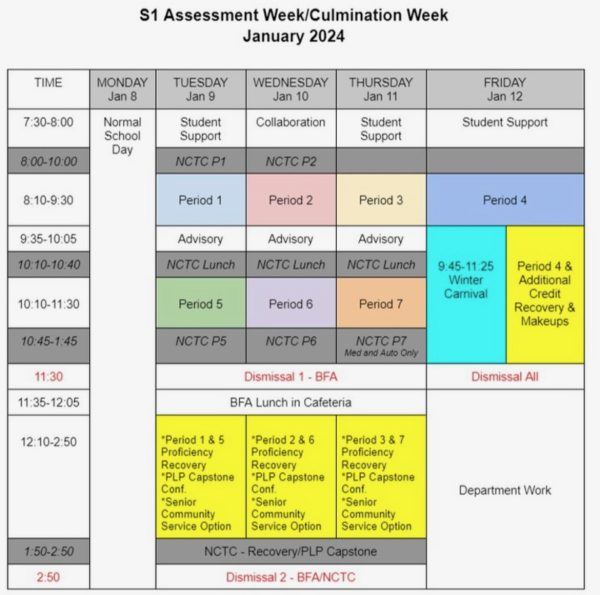

The Vermont Youth Risk Behavior Survey is a survey administered statewide to all high school students. The results can be broken down by county. The county survey results reflect indulgence in “risk behaviors” of Franklin County high school students. The responses from the community’s girls reveal them to be more prone to concerning behaviors than their male counterparts. Conditions such as depression, and the experience of suicidal thoughts or actions are more common among girls than their male classmates, and they are least likely to agree that their community supports them or cares for them.

The 2015 survey shows a 23 percent difference between boys and girls who felt depressed for at least two weeks in a row during the last year. 36 percent of the female respondents answered positively to the inquiry as opposed to only 13 percent of the male respondents doing so.

Why is there such a distinction between male and females feeling supported, happy, and showing willingness to live?

Marlena Valenta (‘17) testifies that these Franklin County statistics are not surprising.

“From my experience in high school, girls feel a lot more pressure, and feel a lot less included because not only do they have boys that are often disrespectful to them, but girls that are often disrespectful to each other and are in competition [with each other]. It’s a time of a lot of change and discovery, and girls feel very much focused – well society causes them to be very much focused – on their bodies and often do not feel adequate. That can really make them feel isolated and upset and lonely and sad,” Valenta said.

Body image, as Valenta argues, plays a large role in the self-esteem of girls and is entwined with the 21st century’s youth being exposed to media.

Judith Breitmeyer, a guidance counselor at BFA and the supervisor for the A World of Difference club commented on the links between body image and depression.

According to Breitmeyer, women and girls are generally more likely to be diagnosed with depression because of the way they are taught to value their physical appearance above their other attributes.

Young girls are also more impacted by exposure to media such as fashion advertisements, tabloid and diet culture, and social internet platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat, and Twitter.

“Body image has a huge role. It has to do with all the media and what we’re focused on and bombarded with from the media every day. Our school is a part of that culture, so for young women to not feel good about themselves, they’ve probably had that reinforced by guys, by other girls, hearing their mothers not being happy with their bodies, it’s all of that, and then just add all the media,” Breitmeyer said.

The 1990 article “Why Girls Are Prone to Depression” from The New York Times by Daniel Goleman examined this subject.

“‘I think that adolescent girls’ preoccupation with how they look accounts for much of the jump in depression for girls at puberty,’” Dr. Betty Merten, of The Oregon Research Institute said in the Times article. ”‘Body image is a huge part of how girls think of themselves and of their self-worth.’…’‘If adolescent girls felt as physically attractive and generally good about themselves as boys their age do, they would not experience so much depression,’” Dr. Lewinsohn of Oregon Research Institute said, supporting the former in the Times article.

The 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey shows that 30 percent of Franklin County’s male respondents were trying to lose weight while 61 percent of female respondents were, aligning with the near 30 percent gap between the rates of depression between each sex.

The preoccupation with the body image begins as young as age 11 in girls, as British Broadcasting Company finds in their 2014 piece, “Young Females More Vulnerable to Depression.” “Before the age of 11, girls and boys have more or less equal rates of depressive symptoms and depressive disorders. However, between ages 11 and 15, girls’ rates of depression rise steeply while those for boys increase only slightly,” BBC wrote.

Breitmeyer’s expertise aligns with their findings.

“Traditionally, what we do know, is that women and girls’ self-esteem plummets during middle school and doesn’t start going back up for a while. We also know that women in society are feeling less empowered, we are less empowered than men; we make less money and we’re treated very differently,” Breitmeyer said.

Valenta complies to this in her testimony of personal experience.

“Really, I think a girl at [age 11] really does feel like her most important asset is her physical appearance. I think that this should be changed, and given other things that they can be appreciated for and that will help with their feelings of inadequacy. Because really, emotionally and mentally they are adequate, but they’ve been trained to focus on their physical attributes,” Valenta said.

With proper context, it comes as no surprise that there is such a large distinction between the happiness of girls and boys in Franklin County.

But how do these feelings affect adulthood? Is it simply a teenaged phase in which girls experience higher amounts of detriments due to sexist societal norms?

The answer is no; feelings of physical inadequacy follow girls into their adult lives.

“The higher rate of depression persists through adolescence and into adulthood, at which point women are twice as likely as men to be diagnosed as depressed,” Goleman wrote.

Breitmeyer, beyond working in school, has also had experience in private practice counselling grown women.

“I’ve probably met one woman that said she felt good about her body. That’s obscene,” Breitmeyer said.

The impact from the media creates a more intense pressure on girls to conform to certain versions of themselves, or even figures that don’t even exist (such as “Photoshopped” models). These poor self-images lead to the areas of risk behaviors such as depression and self-harmful activities that girls lead in throughout the Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Valenta is currently working with Breitmeyer and other faculty members to bring awareness to this issue. The group is exploring the possibility of a school day being devoted to learning about the origins of sexism and how they are prevalent in the modern day, and specifically in the school, although no definite plans exist at this time.